This magnificent and important polychrome painted vase is one of a group of vases that has been identified by an individual (anonymous) artist. The group is identified as the “Fenton School” as after its namesake vase in the collection of the British Museum (collected in the late 18th century in the area of Nebaj, Guatemala).As a child, in the mid to late 1960s, I remember my father, Edward Merrin, displaying this magnificent vase in our house. He had two vases in his private collection, this war vase and a carved vase now in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. The painting is beautifully done with the lines of the figures bold and elegant. This is the last one of a group of six vases still in private hands.

The group consists of six vases and one shard: The Fenton Vase at the British Museum; K558 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; K2206 at the Museum für Volkerkunde in Berlin; K1392 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; a vase at the Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala City; and a fragment in the same style, current location unknown.

Four of the vases illustrate scenes in which tribute is received; two display the acquisition of captives. In addition to sharing a distinctive style, several present the same cast of characters, identified by appearance and/or inscription. An analysis through first-hand inspection and literature review by Samuel Merrin reveals why this piece is truly a spectacle of Maya art.

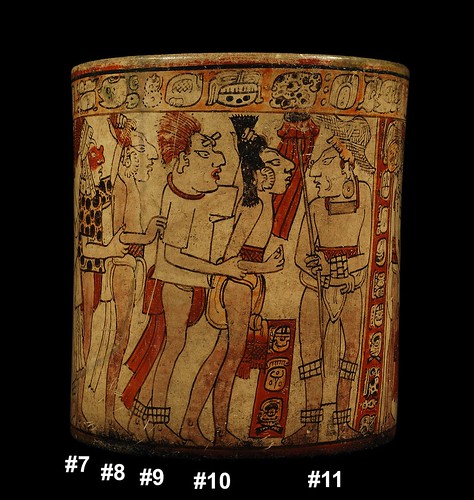

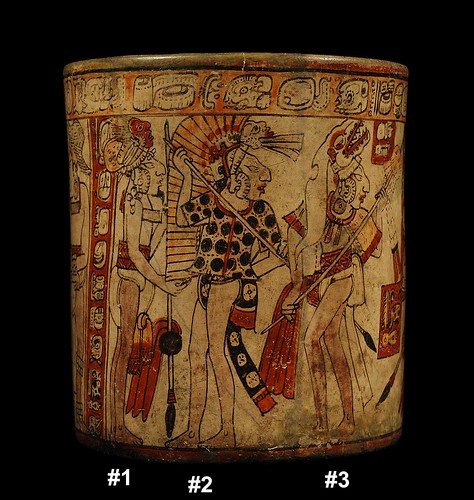

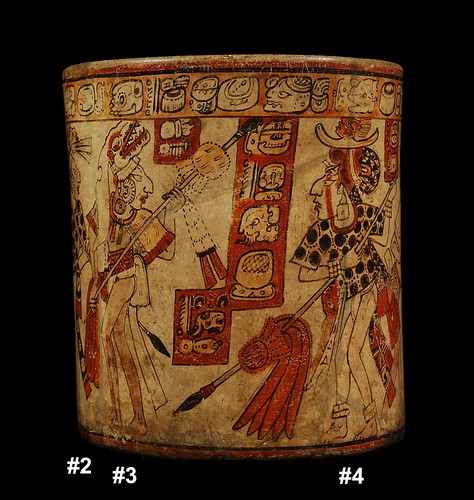

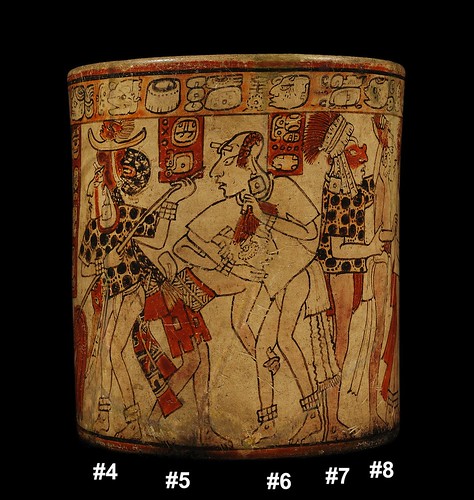

The Merrin vase is painted in black, red, and orange on a cream ground with a thin wash over some figures to indicate a deeper skin tone. The style is bold, assured, and distinctive. In The Maya Scribe and His World, Michael D. Coe has assigned numbers to the figures on the rollout, starting with #1 to the right of the vertical glyph band that acts as a wall and a visual stop.

Eleven figures are arrayed in a scene of battle. Three of the victors grapple with or grasp three captives by the hair and present the captured warriors to figure #11, wearing an unusual straw hat. Meanwhile, the battle proceeds to the left.

Coe distinguishes the two warring factions by their ear ornaments: the losers, perhaps a revolutionary faction, wear floral ear ornaments. Thus the three figures on the left, #1, #2, and #3, are still engaged in battle with the protagonist, figure #4 who wears a jaguar skin tunic with false sleeves, a net headdress surmounted by a brimmed hat with a trophy head finial, and a trophy head ornament on his belt.

(The same type of shirt is also worn by figure #2 and figure #7.) He, alone, has a vertical band of orange facial painting running from his forehead to his jaw. (One of his cohorts, figure #7, has a thick horizontal band forming a half mask in the same orange tone.)

In Lords of the Underworld, Coe posits that the scene on our vase occurs on the day 2 Akbal within a Katun 7 Ahau. The Berlin vase (K2206) seems to represent an earlier point in the same fray, before captives had been taken. This depicts twelve figures in battle in a much more frenetic scene. Here, the protagonist seems to be figure #8. With his distinctive profile and vertical stripe of facial painting and wearing the identical jaguar skin shirt, this figure appears to be identical to the protagonist on our vase and therefore the same historical personage. Coe further states that figure #3 on the Boston vase who kneels before the ruler in the palace scene while presenting offerings of cloth, may also be the same individual. The vases were commissioned to celebrate his exploits.

The glyphic inscription on our vase is as beautifully painted as are the figures. An inscription in the vertical band with a small step, to the left of the main figure (figure #4) states “here it is dedicated, this vessel for fresh cacao”. The glyph for cacao is seen above the head of figure #6. It is an anthropomorphic fish face (ka) followed by a double stacked glyph (wa) creating the sound “kakawa”. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that this vessel was actually used to drink chocolate. The inscription just serves to show that it is a sacred vessel. The additional glyph in the small step on the bottom of the band is figure #4’s “penis title”, a moniker of prowess. The name Ix Balam (literally, “jaguar jaguar”) appears on the vase. This may be the name of the owner. The patron who commissioned this masterful work of art may be Shiyaj K’awiil, as identified on the Boston vase. These two repeat some of the captors and captives.

Whereas the outcomes of war – torture, sacrifice, and the presentation of captives – often occur as subject matter on Mayan art, the depiction of battles themselves is considerably rarer. When it does appear, it is more likely to be in a large-scale format, such as monumental stone sculptures (stelae, steps, and lintels) or murals. This is what makes this vase so special in the eyes of Samuel Merrin and other specialists of pre-Columbian art.

Scientific analysis has shown that the Fenton Vase was made in the area of Nebaj, Guatemala. Located between the Maya lowlands and the Guatemala highlands, the Department of Quichė, in which one finds Nebaj, lacks both monumental sculpture and mural painting. The local Maya nobles, in seeking to emulate the lords to the north in the lowlands, commissioned vases, a portable art form. A painting master developed a distinctive style to record the exploits of his patron.

The vases were presented to nobles in exchange for payment to the Maya lord; thus the vases solidified local allegiances. In tune with the appreciation of Samuel Merrin, this vase has been published and discussed in over a dozen major works, but an early appearance was in a publication of the '70s by the Edward H. Merrin Gallery, New Acquisitions: Pre-Columbian Art of Mexico and Guatemala.

For a 360° video of this Mayan vase visit YouTube: A Samuel Merrin Favorite. Or for more information, follow to the Merrin Gallery's Facebook for detailed specifications.

No comments:

Post a Comment